How can we differentiate natural climate variation from true climate change? What are the main causes? And is there a solution?

With heated debates, the early 70s were marked by bringing up the subject of ‘climate change’. The topic, which was previously exclusive to scientific circles, fell on the lips of journalists. The change was driven by transformations in society and global politics, this included the growing strength of the environmental movement and supersonic travel. In addition, a series of agricultural problems and increases in food prices required urgent explanations from authorities around the world.

Increasing visibility, climate change research received funding, which culminated in the first World Climate Conference in 1979. The event influenced the unfolding of environmental policies in the new decade, the 80s brought a new phase to climate change. The creation of the IPCC in 1988, for example, marked a crucial moment in the development of scientific communication on climate change.

From that moment on, several conferences and agreements were held with a focus on climate change (Conference of the Parties, for example). However, these events often use technical language aimed at experts and decision-makers, which leaves the general public out. This means that many people still do not understand what climate change is, if it is really happening and how it impacts our lives.

Do you want to find out clearly what is happening to our planet? Keep reading to understand everything about this phenomenon!

1. Climate is different from weather

The terms ‘climate’ and ‘weather’ are commonly confused. Both take into account factors such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, among others. However, the concepts are different.

While time is something more ephemeral — daily or even modified with each passing hour — climate is a constant. When we say “Today is cold”, we refer to the weather, that is, what we are feeling at that moment. When we say “Piracicaba is hot”, it is the climate we are talking about.

For a climate to be determined, it is necessary to monitor several factors and observe a repetition of behavior for at least 30 years. These factors are: precipitation, temperature, atmospheric pressure, winds, air humidity, solar radiation and insolation.

That is, the climate of a place is defined only after a pattern in the factors has been observed for a long time. With this, it is understood that the modification of the climate also only materializes after the passage of this long time with the different pattern. In other words, climate change did not happen now, it was not “overnight”.

The naming that climate change is happening occurred by tracking the variability of factors for more than 30 years. Scientists have observed enough changes in global temperature and precipitation to reach such a conclusion.

2. Global warming is the cause of climate change, not the consequence

Another confusion of terms that happens a lot is the doubt between what climate change is and what global warming is. Are they the same thing? Is one worse than the other? In fact, climate change is a consequence of global warming.

Global warming is the increase in the Earth’s average temperature caused by the excessive accumulation of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere. The greenhouse effect, in turn, is a natural phenomenon and essential for life, as it keeps the average global temperature around 14°C. Without it, the planet would be cold and inhospitable, with temperatures close to -18°C.

However, the intensification of emissions from human activities — such as the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation — has increased the concentration of these gases. The main gases emitted are carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O), which trap more heat and cause global warming.

This warming unbalances the climate system, causing the so-called climate change. Among the consequences are more intense droughts and floods, melting glaciers, rising sea levels and loss of biodiversity.

“The increase in trapped energy affects the temperature that we measure on the thermometer. But it also affects the winds, it also affects the rainfall regime and has a general effect on the state of the atmosphere.”

Prof. Fábio Marin, professor at ESALQ/USP and researcher at CCARBON.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global average temperature has already increased by about 1.5°C since the pre-industrial era. Exceeding the 2°C limit could push the planet to a point of no return, where impacts become irreversible, such as the destruction of ecosystems and the collapse of agricultural systems.

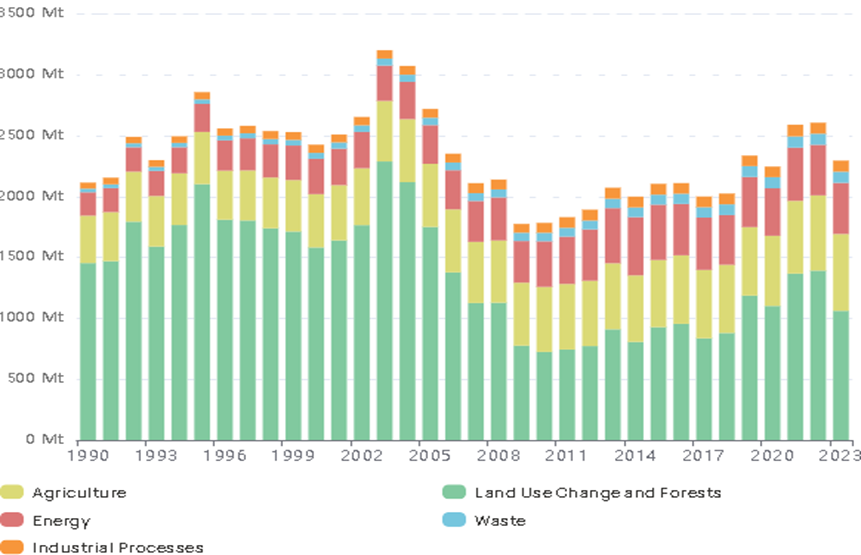

3. In Brazil, 74% of emissions come from agriculture and land use change

According to SEEG – Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimation System, 74% of Brazilian emissions are linked to agriculture and land use change. History shows that the country reached a peak in emissions between 2003 and 2005. The period is marked by the expansion of the agricultural frontier and extensive cattle raising, which rapidly advanced over areas of native vegetation.

A study on agricultural progress in Brazil showed that this growth was driven by the exchange rate policy of 1999 and by the rise in international prices from 2002 onwards. Between the 2001/02 and 2003/04 harvests, the area planted with grains increased by 22.8%. Unlike the previous decade, this increase was driven more by territorial expansion than by productivity gains.

This phase of accelerated growth coincided with the increase in national emissions. After a drop between 2005 and 2012, as a result of deforestation control policies, such as the Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Amazon (PPCDAm), the rates have risen again in recent years. This reflected the weakening of environmental enforcement and the continuous advance of production areas.

Image: CO2 emissions in Brazil, by sector. Source: Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals Estimates System (SEEG).

Within the agricultural sector, the beef chain is the main responsible for emissions — about 1.4 billion tons of CO₂ equivalent per year. However, this same sector has enormous potential for mitigation. Practices such as crop-livestock-forest integration, recovery of degraded pastures, genetic improvements, and optimized diet for livestock can significantly reduce methane emissions. In addition to increasing carbon sequestration in the soil, making livestock more productive and sustainable.

4. The largest emitters are also the most affected

The FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) predicts that, in order to keep up with a world population that is expected to reach 10 billion people by 2050, food production will have to increase by 50%.

However, we can no longer resort to the expansion of areas or the destruction of ecosystems; The limit of environmental tolerance has been reached. The great mystery, therefore, is: how to produce this massive amount of food, emitting less gases and circumventing climate change?

The traditional planning of rural producers is affected due to the recurrence of extreme weather events. The periods of rain, previously expected and recurrent, now become uncertain, and the drought reaches the most critical moments of cultivation.

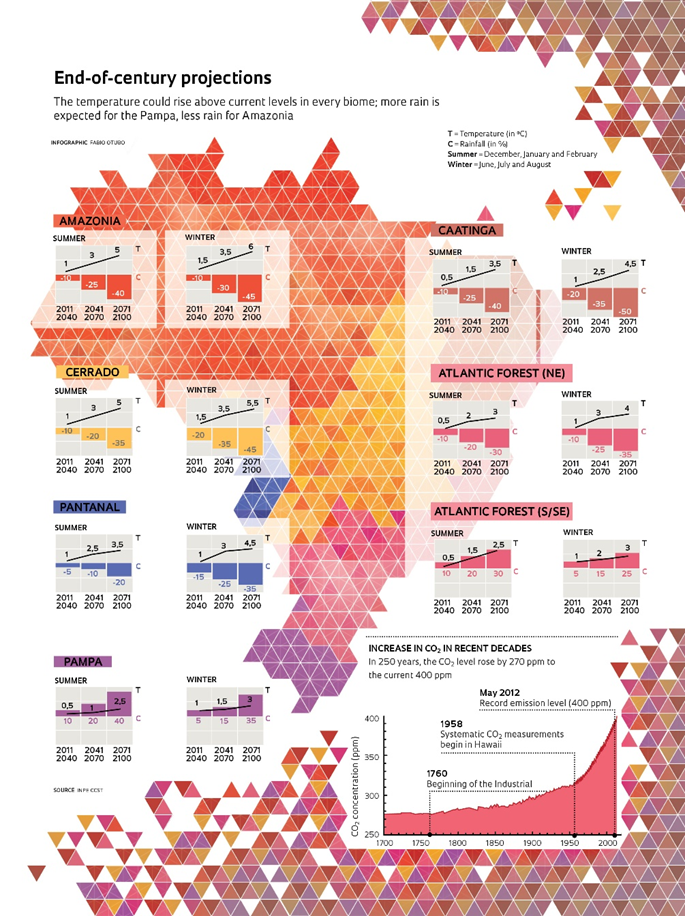

This sudden change is very simple to observe. Whether in temperature peaks above 40°C, which reach even the South of Brazil, or in frosts in traditionally hot regions. Projections, such as the one prepared by FAPESP, indicate that the average temperature may increase by up to 5°C in some biomes, and rainfall by up to 50%.

Image: Climate projections until 2100. Source: Revista Fapesp.

Climate change also acts as an amplifier of the difficulties that already exist in the field. An article published in Science revealed that the climate crisis multiplies environmental damage in agriculture in a dangerous vicious cycle.

Climate stress reduces productivity, leading to land expansion to maintain supply. This generates more deforestation, loss of biodiversity and, consequently, more GHG emissions.

Extreme warming and rainfall accelerate soil decomposition and erosion, which could increase by 66% by 2070, requiring more fertilizer and energy. The ineffectiveness of inputs due to the climate forces the increase of fertilizers, pesticides and the use of groundwater, increasing the carbon footprint of the activity.

In addition, the weather intensifies the threat of pests. Rising temperatures dramatically accelerate the life cycle of insects and pathogens, while water stress weakens plants’ natural defenses. This pressure requires more frequent use of pesticides, which, in turn, accelerates pest resistance, harming agricultural production.

Faced with this complex scenario, the only viable solution is adaptation. It is necessary to invest in technologies and in sustainable and resilient management.

5. Reducing emissions is not enough, we have to sequester carbon

The urgency of the climate crisis requires the world to do more than just decrease greenhouse gas emissions, we need the sequestration of these gases.

“Our agriculture, livestock and forestry sector, in addition to reducing emissions, still has another possibility, and it has been doing so, which is not only to reduce emissions, but to remove part of the excess of this gas to the plant environment, to the soil, which is called carbon sequestration.”

Prof. Carlos Eduardo Pellegrino Cerri

professor at ESALQ/USP and director of CCARBON.

At the 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30), the topic of agriculture as a potential mitigator of climate change was debated. In Brazil, the No-Till System (NTS), for example, is already a consolidated technology that proves the potential of this approach.

An assessment of farms revealed that 27% recovered soil carbon between 80% and 100% in less than a generation. This data reinforces that it is difficult for another sector to achieve what agriculture can do in carbon sequestration.

Therefore, to leverage this mitigation potential, scientific research is key. Several management techniques have been studied, proven efficient and published by our center. Some examples are:

- Fertility management and soil properties in no-tillage systems in tropical and subtropical regions: A review: Comprehensive review on fertility management and soil properties in no-tillage systems in tropical and subtropical zones.

- Quantifying greenhouse gas emissions reduction through enhanced-efficiency fertilizers: A global meta-analysis: A global analysis that quantifies the reduction in GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions achieved through the use of improved efficiency fertilizers.

It is essential that rural producers understand the need for these changes and adopt science-based innovations. The publication and dissemination of these results are the key to making the most sustainable and effective management techniques routine.

___

LEARN

MORE!

The first step to solving the climate crisis is to understand the full picture: distinguishing natural climate variation from human-induced climate change. Understanding the situation, we find ourselves in is essential for us to take action.

References

ClimateData.ca. (n.d.). 30 years of data. Retrieved November 13, 2025, from https://climatedata.ca/resource/30-years-data/

da Costa, M. V., Debone, D., & Miraglia, S. G. E. K. (2025). Brazilian beef production and GHG emission–social cost of carbon and perspectives for climate change mitigation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 32(9), 5245-5258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-025-36022-1

Federação Brasileira do Sistema Plantio Direto (FEBRAPDP). (2025, 11 de novembro). Sistema Plantio Direto é destaque na COP30 com resultados inéditos de sequestro de carbono. PlantioDireto.org.br. https://plantiodireto.org.br/sistema-plantio-direto-e-destaque-na-cop30-com-resultados-ineditos-de-sequestro-de-carbono

National Geographic Brasil. (2025, 10 de novembro). O que é a transição energética, tema urgente da COP30 que coloca o Brasil como exemplo. https://www.nationalgeographicbrasil.com/meio-ambiente/2025/11/o-que-e-a-transicao-energetica-tema-urgente-da-cop30-que-coloca-o-brasil-como-exemplo

Naylor, R., & Shaw, E. (2024). Atmospheres of influence: the role of journal editors in shaping early climate change narratives. The British Journal for the History of Science, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087424001304

Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Jin, Z., Smith, P., Barrett, C. B., Zhu, Y. G., … & Zhuang, M. (2024). Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science, 385(6713), eadn3747. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn3747 Zillman, J. W. (2009). A history of climate activities. World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Bulletin, 58(3), 141. http://wmo.int/media/magazine-article/history-of-climate-activities

How to cite this article: